The process is fairly simple and hasn't changed much in hundreds of years. They're collected, pressed, and dried on the fly.

A typical specimen includes the entire plant, roots and all, when it's possible and makes sense. For samples of trees, shurbs and large herbs, a twig with leaves and flowers is taken.

-First, Daniel records the GPS coordinates of the location where the sample was taken in his fieldbook. He may also photograph the plant and a close up of the flower.

-The sample is laid flat between tabloid-size sheets of newspaper. He writes the specimen number on the paper. Botanists keep life lists of the plants they collect. Every specimen gets a new number. Daniel has just over 10,000 so far. In the field book he records the specimen number, location, a description of the environment (e.g. swamp) the plant's Latin name, its approximate size, co-collector (sometimes me) and any other pertinent details that won't be obvious from the preserved specimen.

-Throughout the day the samples are laid into in a field press which is essentially two slabs of plywood held tightly closed with webbing straps. The specimens stay in the field press overnight to flatten out.

- In the morning, the specimens from the previous day are prepared for drying. They are examined, the leaves are arranged so they look natural and aren't all bunched up. A DNA sample (some leaves) is put in a small plastic bag containing silica gel with the specimen number on it. A sheet of corrugated cardboard is placed between each specimen (still in the newspaper it was pressed in). The package of specimens--there are usually 50 or so--are then bound between two oak latices with straps and placed on a wire rack. Daniel uses a small wire bookcase. A space heater is placed below the cardboard package. The channels in the cardboard are aligned vertically so the water vapor leaving the plant passes through the newspaper and cardboard and is quickly evacuated--like a chimney. The sides of the rack are wrapped in a canvas drop cloth so the heat is retained. The top is left open to allow the vapor to escape and keep the press from overheating. The plants then dry all day while more fieldwork is being done. After eight to ten hours they're dry and the process of "depressing" is executed. The cardboard is removed and the specimens are stored in a box that when full will be shipped to the NYBG. Daniel came up with this process after reading the notes of a botanist in Belize in the 1930s who rigged up something similar, although he used kerosene lamps instead of a space-heater. I'm not sure what the maid makes of all this in the various motels, but sometimes the room fairly reeks of plant life.

- The DNA samples, which will be sent to a lab for analysis, are dried in silica gel in numbered plastic envelopes.

- When the specimens are ready for mounting they are removed from the newspaper and placed on acid free paper. The mounted specimen will be labeled with all pertinent information. Here is an unlabeled Jack in the Pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum):

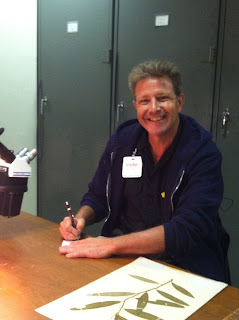

- Botanists have been creating specimens like this for a long time. Here is a specimen of Persicaria (smartweed) from the herbarium at the New York State Museum in Albany. Daniel is the North American expert on smartweeds so we visited the collection and photographed many of the specimens. This one is significant in that it is a "type" specimen. That means this very specimen was the one used by the publishing author as the voucher for his or her name. It was named for the collector Samuel Hart Wright by famed 19th century Harvard botanist Asa Gray. The herbarium staff was very happy to add another type specimen to their collection and Daniel added a note updating the nomenclature to reflect current science (Note the white slip of paper in the lower right).

No comments:

Post a Comment